I love barbeque. Texas is known for our love of the craft and everyone has a favorite place. Ruby’s BBQ is a franchise operated locally in Austin by K & N Management. In 2010, they became the second restaurant to be awarded the Malcolm Baldrige Award for Excellence. While teaching at the Ascension Seton Quality program, I joined the cohort for lunch at Ruby’s and a tour to learn about K&N’s approach to quality.

At the end of the tour, we ordered our favorite meat and sides. I was impressed at the level of thought and process that went into ensuring a customer walks away satisfied. I tasted samples, confirmed the servings weights, and he answered any question. It was clear they wanted to get it right.

When quality is our strategy, our aim is to meet the needs of the customer and deliver service right on the first try. This is not always easy. One tool to learn and improve is a process flow diagram. I love watching teams try to describe and visualize how work happens. Shared understandings are highlighted, unclear steps or steps with more than one “right way” surface, and operational definition confusion is exposed.

There are many approaches to process mapping: draft how you think it should work, map how it actually works, or take it to a very granular level with Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) or value-stream mapping. Teams dive into the tool and learning comes fast. While these are effective change idea generators many times we still have a process that isn’t meeting the customer’s need the first time or is overly complicated.

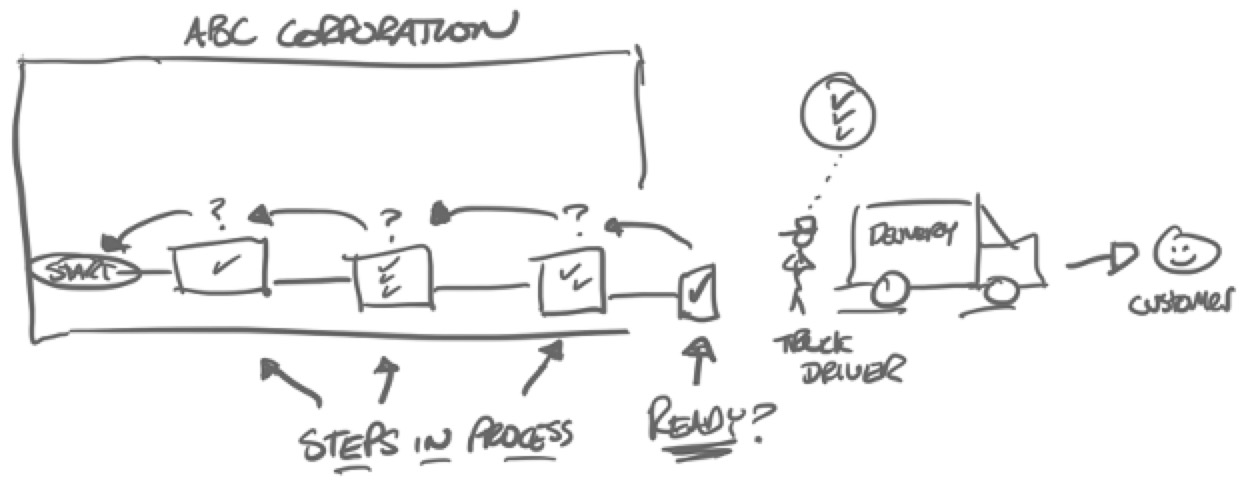

One powerful approach is beginning with the end customer and working backward through the process. Imagine an improvement advisor wants to redesign the process at ABC Corporation that gets the signature product ready to be placed on the delivery truck to go to the customer. If all goes well, the boxes are loaded onto the truck and the driver delivers them to the customer. The improvement advisor wants to reduce waste and rework, so she opts to start at the end of the warehouse process–the truck driver–and work backward to get it right.

“What do you need to see to feel confident these boxes of product are ready to go,” she asks? The driver says, “well, I look for X, Y, and Z.” If they are there, I know it’s good to go.” The improver thanks the delivery driver and goes back to the process step just before. She tells the staff member what the driver told her and asks, “what is required to deliver it ‘X, Y, and Z’ every time?” and he replies, “I need…” Again, our improver takes this information back another step in search of what it takes to get him what he needs for that step. And so on…

For each step, she is learning what is needed and then working backward to learn how the step before can deliver that need every time. In the opening, the Rudy’s BBQ staffer was thinking, “What does it take for a customer to walk away from the counter with the perfect tray of food.” Education improvement advisor David Langford posed this idea from a teacher’s perspective by asking, “What would it take for all the students in your class to achieve proficiency at the end?” A pharmacist might ask, “What does it look like for a customer to be confident and safe when they receive a new prescription?” Each scenario begins with the end customer and works back to getting it right.

Beginning with the need you are trying to fulfill and building a system that meets the need is at the foundation of Dr. Edwards Deming’s provocation to adopt quality as your strategy. Leading companies like Amazon, Apple, and Southwest Airlines are great examples of organizations that start with the need and work to build a system to meet it. Next time you tackle a process, start with the end customer, ask how can we best fulfill their need most times, and work your way backward from there.

—

If this was helpful, share and include me @DaveWilliamsATX. Subscribe to receive a monthly curated email from me that includes my blog posts and Improvement Science resources I think you’d appreciate.

—

Note: I don’t recall the original source (Taiichi Ohno?) and, like the old game of telephone, my telling may have adapted it a bit. It doesn’t soften the lesson.