If you experience chest pain and dial 911 in most communities, an ambulance will respond in a timely and predictable manner to render aid. Many people don’t realize that modern ambulance service is a relatively new public service and began to professionalize in the 1970s. This predictability and reliability was not always the case.

Early in the evolution of ambulance service, the delivery system varied from community to community and so did the reliability, cost, and quality. At that time, a consultant named Jack L. Stout attempted to bring systems thinking and performance management concepts from other industries to the operations of these new ambulance systems.

One challenge he hoped to help communities grapple with was a system strategy to staff and deploy ambulances in an efficient way that allowed access to patients in a predictable time. Unlike the fire service who protect fixed structures that don’t move, police and ambulance services work with populations that shift across their communities as they move from home to work and back again. Also, demand for aid varies in volume across the hours of the day. When and where people need aid is not fixed nor is it smoothly distributed. Stout’s solution…something known as system status management or strategic deployment.

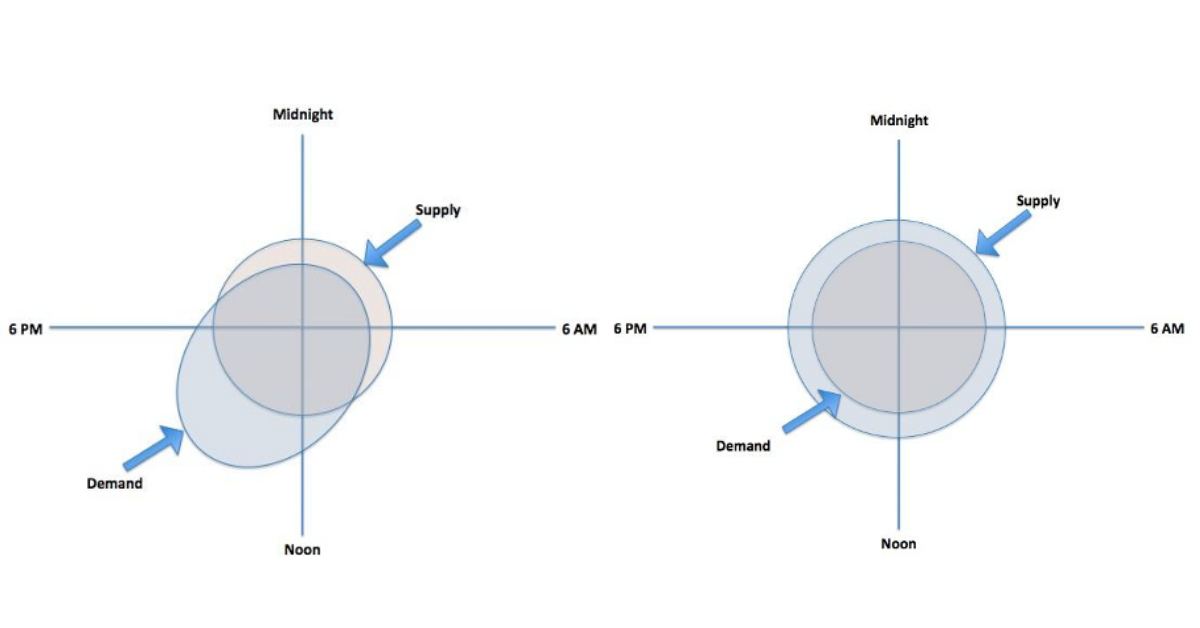

Figure – Matching supply to demand. Left – not aligned. Right – Aligned.

Source: Mike Taigman

The figures above show two different scenarios looking at the relationship of supply and demand across the hours of the day. On the left is a deployment strategy where patient demand is not aligned with the supply of aid. Some hours of the day, too little aid is available and other hours, there is too much, which is waste. On the right is a deployment strategy where the supply and demand are aligned with some added capacity for cushion.

To help community ambulance leaders address this challenge, Stout conducted workshops throughout the 1980s, and many attempted to adopt his theories with mixed results. Some were able to produce reliable access, good quality, and a reasonable cost. Many, however, left the brief training, implemented the method as they understood it, and created unacceptable results- limited cushion of capacity, employees pushed too hard, and poor patient experience. This led to abandoning the approach and claiming it didn’t work. To this day, many ambulance leaders still argue passionately system status management was “voodoo science” and just didn’t work. The approach has not been universally adopted.

This story is interesting because Stout was not introducing a crazy idea. His “system status management” was simply about matching supply to demand. The same leaders who argue against Stout’s approach also demand it and see it as common sense from other services like when they step into a Starbucks or fly on an airline. What has always struck me is how people accepted that the method doesn’t work simply because leaders (decades ago) only learned the concepts in a short workshop and failed to implement it correctly. Does that mean it doesn’t work?

Recently, some have made a similar judgment of improvement methods like the PDSA cycle or Planned Experimentation. This, too, may be rooted in the lived experience of novice improvers who have a basic understanding of PDSA and have tried the approach without experiencing deep learning or results. In the last few years, a few papers (ex, here, here) and other publications have critiqued the use of the PDSA cycle in healthcare, which some viewed as confirming the method didn’t work.

Similar conclusions have been drawn about Planned Experimentation (PE), which is a rigorous approach for testing changes and learning about their independent affect and the effect of the interaction of factors. PE has a bit of a learning curve to understand and do. It has not been as widely adopted as the PDSA cycle. This has led some to conclude PE doesn’t work or isn’t helpful in spite of several peer-reviewed papers including this recent example showing its value.

The PDSA cycle is a powerful method for testing change ideas and learning, as is planned experimentation. Evidence exists in practice and in the literature to support their efficacy. There are also many examples of well-intended improvers learning the basics, trying without fidelity, and then pointing to the method rather than the execution when they do not see results.

As Reed and Card conclude in their paper on PDSAs, “Ultimately, we argue that the problem with PDSA is the oversimplification of the method as it has been translated into healthcare and the failure to invest in a rigorous and tailored application of the approach.” How similar this feels to the opening example of matching supply to demand!

If improvement were easy, everyone would do it. The science of improvement and the tools and methods like PDSA, Shewhart SPC charts, and planned experimentation are all very powerful when one takes the time and effort to learn and then applies what they learn with fidelity. Before deciding something doesn’t work, ask if you’ve really made the effort to learn and understand the method and whether you have attempted to apply that method with fidelity more than once? Committing to learning more deeply will enable you to understand and apply these methods and achieve great results for those you serve.

—

If this was helpful, share and include me @DaveWilliamsATX. Sign up here to receive a monthly email from me that includes all my blog posts and other Improvement Science resources I think you’d appreciate.